Anyone that works in schools understands the immense challenges facing young people today. Mental health issues and school attendance are at the forefront of everyone’s minds.

Absenteeism is considered such a large issue that in England there is a national drive to improve it, and a TeacherTapp survey from last year shows clearly that teachers think future education policies should be public service based, with the first three all focussed on mental health. And like most complex issues, there are likely to be numerous causes, which naturally leads to a constant debate about the solutions.

One common line of argument is that the increase in school avoidance is due to anxiety caused by authoritarian school regimes, their strict uniform rules and liberal use of isolation rooms. In fact, this line of argument was used in all three of the points in this recent article in the Guardian. Unsurprisingly, and to a certain extent understandably, there is a significant movement of people – teachers, psychologists, consultants and journalists – looking to change this. Most commonly there is a desire for total system change, outlawing certain practices in a reimagined approach to schooling, as this would alleviate student anxiety and increase school attendance.

This raises two important questions.

- Do authoritarian behaviour policies actually lead to an increase in mental health issues, specifically anxiety?

- Is removing such policies going to have a positive impact on anxiety?

Whilst obviously linked, it is important to ask both questions separately. We may be able to find evidence to support one but not the other. But both are crucial in the debate because they provide information about what we should do to support our clearly struggling students.

The link between behaviour policies and anxiety

The short answer is we don’t know if there is a causal link. As any Sixth Form Psychology student will be able to tell you, mental health is wickedly complex. There are all kinds of biological, cognitive and sociocultural factors that are linked to mental health issues.

I’ve written previously about how the link between trauma and mental health issues is not clear. This is equally true of anxiety disorders too.

There is a decent amount of evidence showing that there is a genetic component to both panic attacks and generalised anxiety disorder. There are some studies, here and here, that suggest potential genes that predispose people to anxiety.

We have known for some time that anxious individuals are likely to overestimate risk as well as spend longer processing threat-related information. And more recent studies show that dispositional factors influence the likelihood of panic attacks in response to threats.

We also know there are other sociocultural factors that affect anxiety. Many will not be surprised to know that there is a correlation between time social media use and symptoms of dispositional anxiety. Although looking at adults, there is also a correlation between ‘upward social comparison’ and anxiety, and a correlation between lower self esteem and social media use, suggesting that social media has a significant role to play in anxiety issues.

So before we even get to the question of whether authoritarian behaviour policies might be having an impact on anxiety in children, we need to be aware that there are a host of other likely aggravating factors.

But that doesn’t mean the policies are not having a negative impact.

As I’ve mentioned, there are plenty of examples circulating the news and on Twitter (X) about how students have anxiety as a result of specific behaviour policies. I do not want to link to the stories as the point of this post is not about the people sharing the information, nor the students with anxiety. So I hope that readers are aware of the stories. If not, please message me and I’ll send some links.

I also think it is important at this point that I do make a few things clear

- I fully believe what the students/sharers are saying. There is no reason to believe anything is false or made up.

- It is important to give a voice to the vulnerable. People with a voice should absolutely use it in support of those without one.

- I don’t want to dismiss anecdotes. Just because something is anecdotal, it doesn’t make it unworthy of being heard. To extend Hitchens’ razor – that which can be asserted with anecdote can be refuted with anecdote. But that is a (mitigable) research method issue. More importantly, dismissing anecdotes means silencing people. Just because something is anecdotal doesn’t make it untrue. And sometimes the best way to get more evidence that shows a general trend is to start with anecdotes and stories.

So let’s look at how big the issue may be…

Tip of the iceberg, or small subgroup?

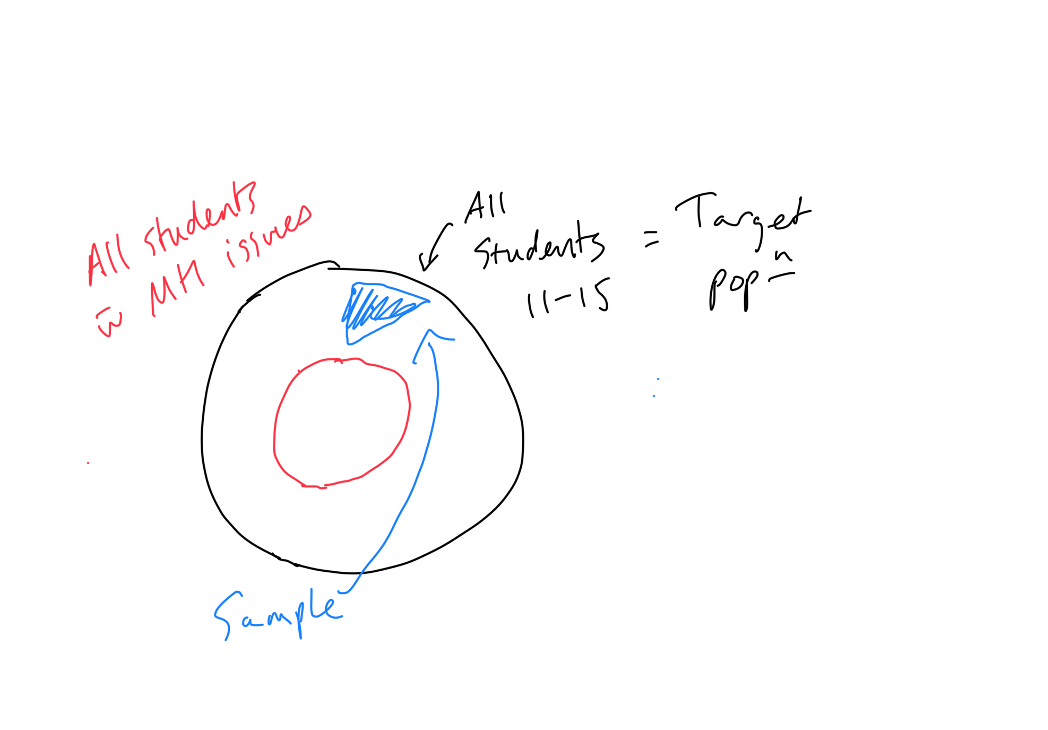

Any piece of research involving humans will require a sample. We are not going to conduct a population wide poll or experiment any more than we would test drugs on the entire population.

We use samples in the hope they represent the important and relevant characteristics of the target population we are interested in, so that any conclusions we draw from this sample can then be applied to this target population.

We want to find out the views of a particular behaviour policy on the mental health of young people between 11-15.

The largest circle represents all young people between 11-15. It’s our target population. The segment represents the sample of people we are asking. We technically, probably, could ask all young people within this target population, but the time, cost and sheer logistics would be unnecessarily prohibitive.

So far so good. We know we aren’t going to ask everyone, so who do we ask? Do we just go to one school and ask 50 people? 100? Even with no formal research training, I think most people could see why this might not give us a representative sample.

There are all kinds of characteristics we may wish to account for. Age, race, gender, socio-economic group, type of school, nationality, location, etc. etc.. And this is before we’ve even looked at characteristics that are specific to our investigation. The above characteristics should be taken into account for any survey on young people, irrelevant of topic.

But if we are looking at mental health, we also need to take this into account.

So back to our circle. The larger circle is still the target population – all 11-15 year olds. The second circle represents all those people with diagnosed mental health issues – it is a subgroup.

Now imagine our sample only asked people from the highlighted segment.

We could have a huge sample of thousands of students from all across the country with all kinds of backgrounds. But the information would be relatively useless. Why? Because here we would have only asked people that have no history of mental health issues. Our sample is not representing the target population with regards to an important characteristic. We may be missing crucial information and draw an incorrect conclusion. In this example, we no longer have a target population of 11-15 years olds. Our target population is now 11-15 year olds without a diagnosed mental health issue.

Importantly, the converse is also true. Imagine our sample now only asked people from within the smaller circle.

Our sample now doesn’t represent the target population, but in a different way. Again, we may be missing crucial information and draw an incorrect conclusion and again our target population has changed. It is now 11-15 year olds with a diagnosed mental health issue.

Neither of these scenarios is inherently bad. But in both cases we are limited in generalising our conclusions to the entire population of 11-15 year olds, meaning any conclusions may not apply to them.

We want our sample, in addition to the general characteristics listed above, to have students that represent students inside and outside the small circle – a cross section. So we must work hard to ensure this is the case. And, at least in theory, we should also account for any other factor we may think will influence student attitudes.

We want out sample to look like this

There are many ways to make samples more representative, with most coming down to the type of sampling method and/or the size of the sample. It would normally take me a fair few lessons to teach these aspects of research methods to my psychology classes, so I think it’s probably out of the scope of a blog post. But if people are interested, perhaps I’ll write about those next time.

So why is this important?

There are lots of reasons, but a main one is it allows us to understand the extent to which we can generalise conclusions. We shouldn’t generalise to a target group not accounted for in our sample. The vast majority of research has a limited sample, sometimes by design and sometimes as an unavoidable occurrence. It is not an inherently bad thing, so long as researchers accept it and understand what their sample represents, and what legitimate target populations are.

An obvious example would be when we talk about many of the EEF guidance reports. They are limited in their generalisability because they often only consider research on students with English as a first language. This isn’t an issue at all, the EEF fully acknowledge this, but it does mean that conclusions can only really be applied to students with English not as an additional language.

Research should really say something like: our findings suggest X for population Y (green circle), more research is required to see if this is also the case for population Z (blue circle).

Sample limitations can be offset by other pieces of research using different samples, so when taken together, we can start to build a picture of applicability to population Z. This is one of the reasons not to ignore anecdotes; at some point we might have 1000 of them! I’ll come back to utilising other research later.

Unfortunately, though, research is not often communicated as such. Research only applicable to population Y is extrapolated to population Z without any justification. It doesn’t mean it isn’t the case, just that this research doesn’t demonstrate it.

And when this is done intentionally, it is really poor practice. Practice my psychology students would hammer. They would, quite rightly, highlight a sampling issue – we don’t know if the sample is representative of the target population, therefore our conclusions should be limited.

Is this the case with behaviour policy-induced anxiety?

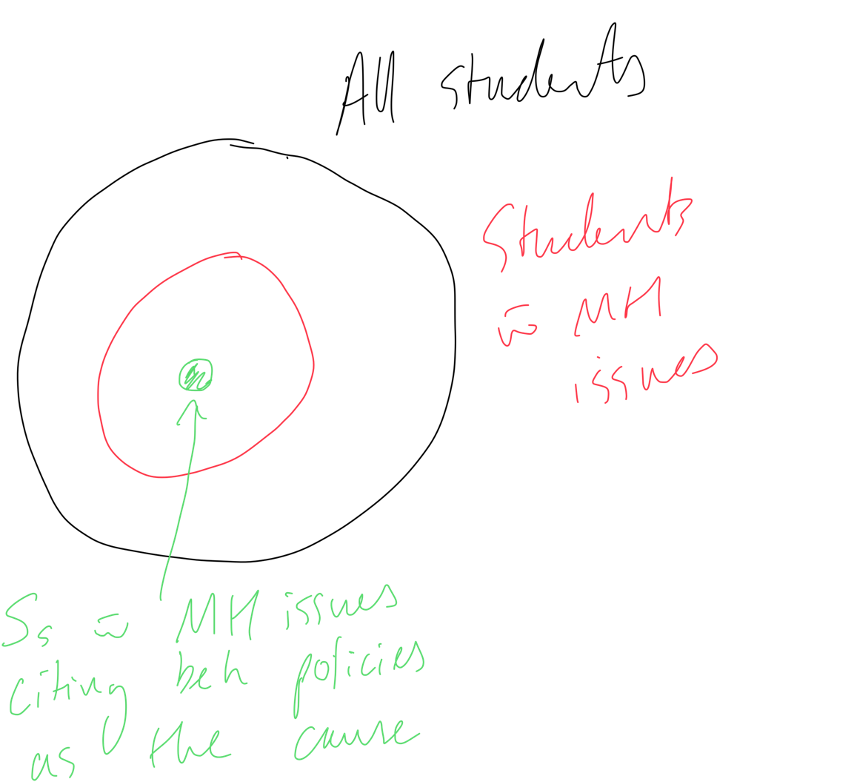

Let’s look at the sorts of policies listed above that are suggested to cause mental health issues. If we go back to our population circles, it would look something like this.

Of all the students in England, many (too many) will have mental health issues (red circle). Of these, some (green, a subgroup) will be claiming that the behaviour policies are the cause. In actual fact, it could be like either of the circles below or something in between – we simply do not know exactly how big the subgroups are – but we do know that the ones we hear about must be a small subgroup.

Even if we grouped all of the individual stories from the prominent people on Twitter and news websites, we wouldn’t have very many individuals claiming mental health issues as a result of behaviour policies. Certainly only a tiny percentage of all students.

And we cannot even be sure the sample we see on social media is in any way representative of students with mental health issues in England, let alone all students in England. We cannot be certain that they have had similar experiences of behaviour policies. We don’t know their medical backgrounds, race, gender, socioeconomic status etc.. The latter being of particular importance given the findings of the Millenium Cohort Study that shows those in the lowest income bracket are 4.5 times more likely to experience mental health issues than the highest.

Which means the actual cause may be something else entirely.

To reiterate, it doesn’t mean we ignore this sample. It may, in fact, represent what the population thinks/feels, but we do not know that it does. And if we do not know, we can not, and should not, make suggestions based on this sample that will affect change on an entire school system.

All we can conclude at this time is:

- Many students need more support and might need some form of alternative to their current school provision.

- It would be worthwhile conducting more research into the effects of behaviour policies on student mental health, ensuring we obtain a representative sample in our research

If this is what were being proposed, I think most people would be supporting it wholeheartedly.

Another way to think about this being a sampling issue is to consider how those making the argument would respond to the same stories but from the opposite view. I.e. If we had lots of stories about students who said their mental health is unaffected (or improved) as a result of the behaviour policies.

I would hope the response would be something like

“This doesn’t represent all students. Some are clearly negatively affected, so let’s not ignore them”.

And they’d be correct. So I think it is only fair that we use the same logic the other way around.

“There are some students negatively affected by the behaviour policies, but many are not, so let’s not ignore them.”

Because we do know lots of students do not have mental health issues as a result of these policies.

To summarise, we know three things:

- Some students have mental health issues, citing behaviour policies as an aggravating factor.

- Not all students exposed to these policies have mental health issues

- Not all students with mental health issues cite behaviour policies as a factor.

So the question should shift away from:

‘Do behaviour policies cause mental health issues?’

We know this question is difficult to answer. It is therefore probably worth focussing on an action with a question like:

‘Even if the behaviour policies do cause mental health issues in some students, would a change in policy be beneficial for these students and/or all students?’

This acknowledges the need of some students, as well as considering those currently without a need.

Because making a change to meet the needs of some students is potentially not a neutral decision for others. Can we be sure there will be no negative effects for them?

(….Have we even asked?)

Utilising other research

Earlier I said that we can mitigate some sampling issues by having similar research with different samples.

How could we do this? One way would be to get information about other students that have mental health issues and see if these are also caused by the problematic behaviour policies. If these really are the main problem, we would expect to see similar patterns of evidence across all our studies.

Let’s do it. I’ll focus on Germany, because I know it well.

A recent Focus article suggests 15% of children in Germany have an anxiety disorder, whilst another suggests potentially as many as 5% of children aged 5 to 11 have school related anxiety. This article from 2009 says 20% of all children suffer from school anxiety! From 2009!

This report from one health insurer published in Nov 2023 shows that despite some positive trends about new diagnoses, the overall situation is not good for depression and anxiety disorders, especially amongst 15-17 year old girls, with over 6% having anxiety, 7.5% having depression, and a 3% comorbidity.

This study published in 2022 found that 44% of students have anxiety about classwork and performing well in comparison to classmates, 30% worry about going to school the evening before and more than 25% have psychosomatic symptoms before exams and tests. Interestingly, only about 12% have fear of bullying. These figures are frightening.

Mental health issues are clearly a significant problem for children in Germany.

And yet…

In Germany, the vast majority of schools do not wear uniforms. I’d even stick my neck out and say that 99.9% of all state schools do not have a uniform, but that is just an educated guess backed up by generic information on wikipedia. This means that no school has isolation rooms for haircuts, or detentions for minor uniform infringements. The law allows students to go to the toilet whenever they want. There is also no Ofsted, no performance tables, there’s loads of teacher assessed grading, and excellent vocational pathways. So the issues highlighted as causing anxiety in the Guardian article I cited above, do not really exist.

And therefore the mental health issues in Germany have nothing to do with authoritarian behaviour policies. They cannot.

Of course, this doesn’t exclude the possibility that if exposed to authoritarian policies children in Germany would cite these as an issue, just that they are not a cause of the issues observed.

But this does mean that when taking into account students across England and Germany, authoritarian behaviour policies are only affecting a very very small subgroup of children with mental health issues.

There could be all manner of reasons for the differences between students in England and Germany. Perhaps there are actual significant, fundamental differences between children in the two countries? Or perhaps there are multiple factors that cause mental health issues, behaviour policies being one, which is a non-existent cause in Germany but the most salient in England?

I doubt anyone really believes the first explanation, and I think most would accept the second.

But here’s the rub. If we are to accept the second explanation and reject the first, we must also accept that even if the behaviour policies were changed in the UK, i.e. no isolation rooms or detentions for uniform infractions, the likelihood is that there would still be persistent mental health problems for children in England. Because there are clearly other factors that are influencing mental health.

We have a clear example of a country that doesn’t have such behaviour policies and yet still has a huge issue with anxiety in students. And it isn’t just a Germany issue. USA and Canada both show similar trends with regards to the mental health of children, again with no discernible authoritarian policy with regards to uniform etc.. So what evidence is there to suggest England would be different?

So unless we can be certain that the behaviour policies are the only or biggest cause, removing them is unlikely to resolve the problem. Moreover, what are the other potential consequences of doing so, both for those with and without anxiety?

And that’s why sampling is important. How do we know if it is the tip of the iceberg, or a small subgroup? And how would we know what other students think of the policies?

Without understanding the limitations of our sample, we don’t know to which populations we can apply our conclusions. We may end up changing things that make no difference or even make things worse in a different way for the rest of the target population.

Perhaps we do indeed need an entire system change, or maybe just more support for the individuals that need it? But if we don’t ask a representative sample in the first place, we’ll never know.

So if people want to argue to change behaviour policies on ethical, moral or ideological grounds, have at it. But until we have sufficient evidence from a decent sample, let’s not extrapolate information from a small subgroup of people and apply the conclusions and solutions to all students. That’s disingenuous at best, malpractice at worst. And it’s not a good basis for making decisions, whatever one’s opinions.